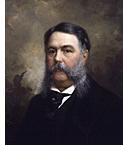

Chester A. Arthur (1829-1886)

American lawyer, politician, 21st President of the United States (1881-1885).

Born in a small cabin in Fairfield. The son of the Irish-born Reverend William Arthur and his Vermont-born wife, Malvina Stone Arthur, young Chester and his family migrated from one Baptist parish to another in Vermont and New York. The fifth of eight children, Chester had six sisters and one older brother. Before beginning school in Union Village (now Greenwich), New York, he studied the fundamentals of reading and writing at home.

Arthur entered Union College in Schenectady as a sophomore in 1845, where he pursued the traditional classical curriculum, supplementing his tuition by teaching during winter vacations. Though not an outstanding student, he graduated in 1848 in the top third of his class and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

After college, Arthur spent several years teaching school and reading law, but he was clear about what he wanted to do with his life. He sought to reside in Manhattan as a wealthy lawyer and public servant, living the life of a true gentleman. With such goals in mind, he passed the bar in 1854, and, using his father’s influence, gained a clerkship in a New York firm headed by the prominent Erastus C. Culver.

Arthur’s public profile was advanced in the firm’s defense of Elizabeth Jennings, a black woman who had been forced off of a Brooklyn street car when she refused to leave the section reserved for whites (her civil disoebience predating Rosa Parks by over one hundred years). Arthur, now a partner in Culver’s firm, won $225 from the streetcar company and $25 from the court. The case forced New York City railroad companies to seat black passengers without prejudice on their streetcars.

When the Civil War broke out, Arthur was ready for duty. In 1858, he had joined the state militia principally out of a desire for companionship and political connections. In a rush to staff key positions, the Republican governor appointed Arthur to be engineer-in-chief with the rank of quartermaster general in the New York Volunteers. He served in that post with great efficiency, obtaining the rank of brigadier general. Responsible for provisioning and housing the several hundred thousand soldiers supplied by the state to the federal cause, as well as for the defenses of New York, Arthur dealt with hundreds of private contractors and military personnel. The military service played to his advantage; he gained a reputation for efficiency, administrative genius, and reliability.

Although eager to serve in a battlefield position, Arthur never pressed his case. His wife, a Virginian with family members in the Confederacy, could not tolerate the thought of her husband taking up arms against them. Moreover, his sister had married an official of the Confederate government who was stationed at Petersburg, Virginia.

Upon his retirement from duty in 1863, Arthur threw himself into his law practice, representing clients in suing for war-related damages and reimbursements. The practice thrived, making him wealthy by the war’s end. He also worked actively for Roscoe Conkling, a New York Republican Party boss and US senator who used patronage and party discipline to advance his power in the state. By 1867, Arthur had become one of Conkling’s top lieutenants. From 1869 to 1870, he served as the chief counsel to the New York City Tax Commission, earning an annual salary of $10,000, a princely sum of money in those days. (In 1870, the wages of a skilled worker ranged from $400 to $650 annually.) Though there is no evidence of Arthur being specifically guilty of receiving graft during a stint as Port Collector (A US Grant Appointment), Arthur did benefit greatly from traditional kickbacks from fees.

Elected Vice President under James A. Garfield in 1880, Arthur became President upon Garfield’s assassination. a newspaper noted that he was “not a man who would have entered anybody’s mind” as a worthy candidate for the office. In fact, as a major player in a spoils system that had reduced civil service to a sinecure-ridden vehicle for rewarding party faithful, he struck many as an icon of all that was wrong with American politics.

As President, however, Arthur rose above his patronage-dispensing past to promote landmark legislation designed to curb the very spoils system that had been the springboard for his own political rise. He also proved to be a foe of other forms of corruption. When, for example, a “pork barrel” bill for public improvements reached his desk, he did not hesitate to veto this measure, which clearly placed catering to special interests above public need.

In 1882, Arthur was diagnosed with Bright’s disease (at the time, a fatal kidney ailment), but he kept it secret. Knowing the condition was fatal, he made little effort to seek nomination for a second term, though he did not oppose efforts by others on his behalf. On the fourth ballot at the convention, he lost the Republican nomination to his former secretary of state, James G. Blaine.

Arthur tried to resume the practice of law after leaving the presidency, but his ill health prevented him from doing much work. The disease had seriously weakened his heart, and he became too frail even to go fishing, which was the great love of his life. His death came at home with his children and sisters near at hand. He was buried with full ceremonies in Albany, New York. His successor as President, Grover Cleveland, was in attendance